AI in week 44

Model collapse

Ik had het eerder al over de verschillende bubbles van AI: de investeringsbubble, de hypebubble en de infrastructuurbubble. De investeringsbubble is makkelijk uit te leggen, die kennen we uit andere tijden ook: op een dag is het geld gewoon op, we kunnen niet alles in AI blijven stoppen. Volgens held Ed Zitron heeft openAI alleen de komende 12 maanden al nog 400 miljard dollar nodig. Ook de infrastructuurbubble is vrij duidelijk, GPUs hebben, in tegenstelling tot bijvoorbeeld internetinfrastructuur die overbleef van de dotcom bubble, een hele korte levensduur, van maar zo'n 1 tot 3 jaar. Dus daar hebben we nadat deze bubble popt niks meer aan.

Maar die derde bubble, de hype bubble, die is ongrijpbaarder. Ik blijf steeds maar weer van mensen horen dat AI nog veel beter gaat worden, zelfs als Sam Altman zelf zegt dat dat helemaal niet zo is, dat hallucineren er altijd bij zal horen. We zijn zo gewend aan technologie die steeds maar weer beter wordt, en we horen dat verhaal ook voortdurend van AI hypers, dat we het blijven geloven.

Echter, onderzoekers oa van Oxford and Cambridge tonen in een recent paper in Nature aan dat LLMs, naarmate ze meer synthetische data gaan inlezen, model collapse gaan vertonen:

Model collapse is a degenerative process affecting generations of learned generative models, in which the data they generate end up polluting the training set of the next generation. Being trained on polluted data, they then mis-perceive reality.

Nu zou het zo kunnen zijn dat het model beter wordt van synthetische data, als die toevallig heel goed klopt, dat geven de auteurs ook toe. Maar, zeggen ze, dat is meestal niet zo:

More often than not, we get a cascading effect, in which individual inaccuracies combine to cause the overall error to grow.

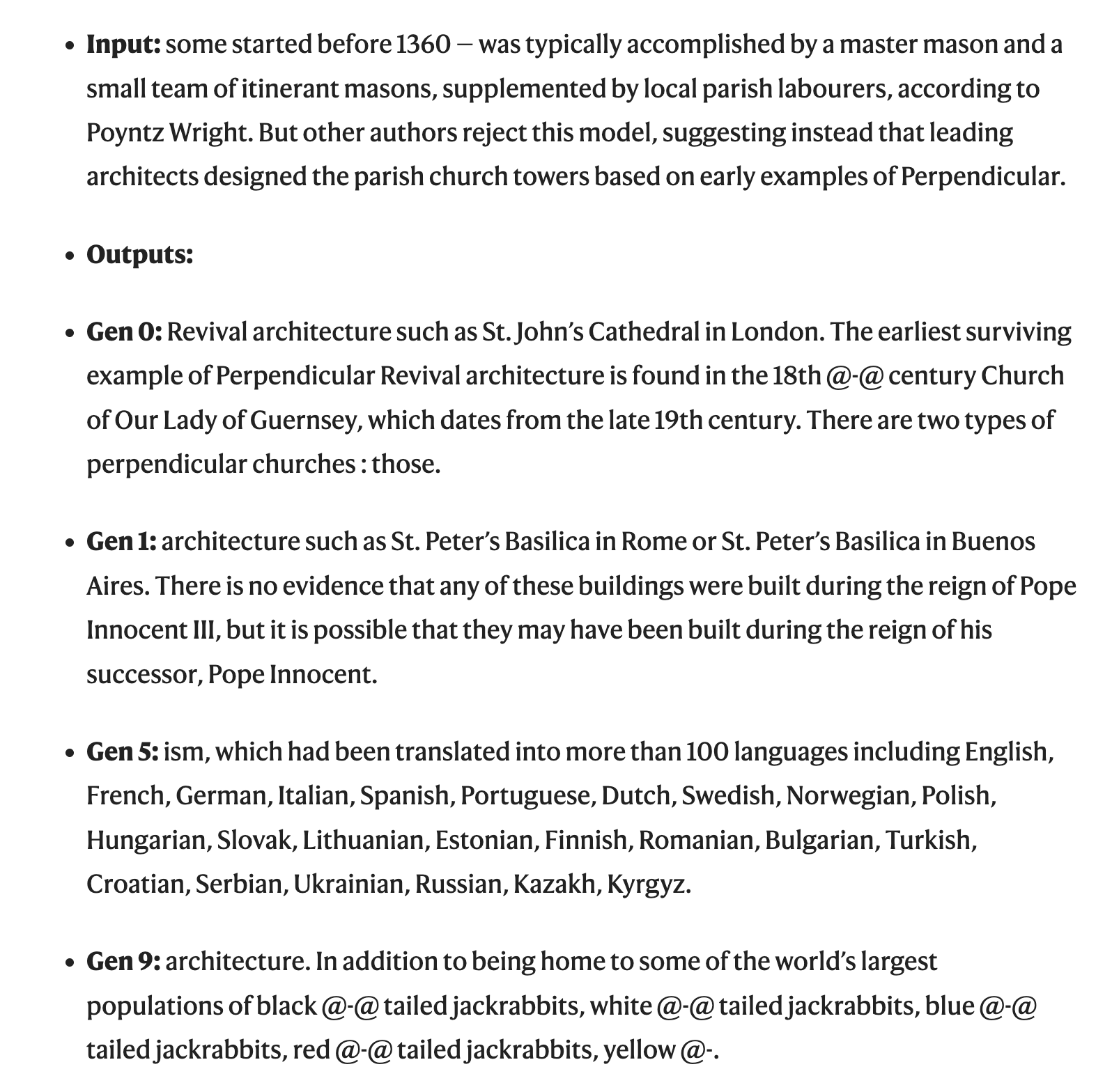

De auteurs geven een voorbeeld dat vrij goed aantoont hoe een zo'n incestueuze LLM zich gedraagt:

Proberen die gekke herhalingen eruit te programmeren, maakt het resultaat alleen maar slechter. En, zo schreef een ander paper, ook LLMs kunnen brain rot krijgen van slechte data (al ben ik niet gek op deze term omdat die nu zo sterk gekoppeld is aan mensen).

De toekomst ziet er niet zo hoopvol uit, want die slechte en synthetische data, daar zijn we nu al bijna! Op de blog van visualiztietool Graphite kunnen we lezen dat inmiddels meer dan de helft van de nieuwe artikelen op internet komt nu al van AI. De dead internet theory, ooit een gekke conspirary theory, begint zo onderhand geloofwaardig te klinken. Google zei immers zelf ook al dat "the open web is in decline".

En dan hebben we het nog over onopzettelijke vervuiling van datasets, al hoewel je je kan afvragen hoe per ongeluk het is als het ongeveer zo duidelijk gaat gebeuren als de Titanic tegen de ijsberg...

Minstens net zo problematisch is onderzoek van Anthropic zelf, nota bene, dat laat zien dat je met 250 documenten een LLM al over de flos kan helpen, onafhankelijk van hoe groot de dataset is waar die op getraind is. Nu is dat volgens henzelf niet erg, het model gaat er hooguit gibberish van praten, maar ze zeggen het toch alvast even, wat vriendelijk toch. Nu lijkt dit mij, in tegenstelling tot de onderzoekers van Anthropic, wel een significant risico, want het ondermijnt nog verder de mogelijkheid om aan goede informatie te komen!

Grappig detail trouwens, de post van Anthropic rendert niet helemaal goed (zie onder) en dan denk ik dus meteen... Is dit een vergiftigd document? Of is het gibberish? Ben ik onderdeel van de volgende test?

Schrijven als 'theory building'

Zoals ik al eerder schreef, mijn onderzoek richt zich tegenwoordig het meest op de vraag waarom de informatica is zoals die is, en welke wereldvisie er naar voren komt in informatica-opleidingen, en daarmee: in de informatica-cultuur.

Dan kan je bijvoorbeeld denken aan de vraag wat er wel en niet tot het informatica-canon behoort. Dat gaat soms over mensen, ik had bijvoorbeeld tijdens mijn studie nooit over Joseph Weizenbaum gehoord en zijn scherpe kritiek op de cultuur van informatica, en op chatbots (maar ja, ik studeerde dan ook tijdens een AI winter), maar soms gaat het zelf over welke stukjes over een onderzoeker we leren kennen.

Deense informaticus Peter Naur kennen we allemaal van de Backus-Naur form die gebruikt kan worden om programmeertalen mee te beschrijven. Maar, hij heeft ook een geniaal paper geschreven getiteld Programming As Theory Building. Het is heel dun, je bent er zo doorheen, maar het staat bol van de waarheden die ook vandaag de dag nog nuttig zijn.

Naur schrijft in dit paper dat als je iets leert, dat dat niet alleen gaat iets kunnen, maar ook over het kunnen uitleggen en verdedigen:

the knowledge a person must have in order not only to do certain things intelligently but also to explain them, to answer queries about them, to argue about them, and so forth.

Dit noemt hij het ontwikkelen van een theorie (theorie is in deze context een beetje een apart woord, omdat het veel verschillende dingen kan betekenen, maar ik ga even mee in deze term):

A person who has a theory is prepared to enter into such activities; while building the theory the person is trying to get it.

Naur beargumenteert in zijn paper dat als je ergens over nadenkt, en ik generaliseer hier even van programmeren naar allerlei soorten denkwerk, dat je dan tijdens dat werk theorieën opdoet over hoe dat iets werkt, maar dat je daarna ook kan uitleggen waarom het zo werkt, of waarom hoe het werkt echt de slimste manier is ervoor.

Nu zijn er natuurlijk genoeg redenen om geen AI te willen gebruiken, verwoestende klimaatimpact–ook deze week lazen we weer over Microsoft die AI-datacentra bouwt en geen enkele verantwoordelijkheid neemt voor de milieu-impact—bias, meer macht voor techbazen die fan zijn van Trump, etc. Maar dit is een veel diepere reden, het systematisch verwarren van de output van werk met wat je opsteekt van dat werk. Ik zag bijvoorbeeld deze op BlueSky voorbijkomen van een professor in de biomedische informatica Todd Johnson:

We spent months doing a careful lit review with help from a librarian, PubMed, and Google Scholar. After we had completed the work and whittled the 7K+ citations down to only 7 that met our criteria, I asked Claude the question we were trying to answer. It found 6 of the 7 and wrote a great report.

Ik vind het vermoeiend om dit te moeten blijven uitleggen, maar als wetenschapper moet je niet alleen kennis leveren, je moet ook staan voor die kennis, staan voor waarom je precies die zeven papers hebt uitgekozen, en niet, met behulp van andere criteria tot andere papers bent gekomen. Juist die uitlegbaarheid mist een algoritme, want die heeft overduidelijk niet maandenlang zitten broeden, wikken en wegen op de juiste papers. Zo'n studie is vaak een iteratief proces, waarbij je criteria soms aanpast omdat je ziet dat ze niet de juiste papers opleveren. Willen we dan werkelijk wat wetenschappers, als we ze vragen hoe ze tot een conclusie zijn gekomen, zeggen: Claude zei dat?

Een algoritme heeft geen innerlijke toestand, geen geheugen, en geen herleidbaar proces dat tot conclusies leidt, dat weten we allemaal want als we weer eens een hallucinatie tegenkomen en doorvragen, staat de AI altijd weer klaar om sorry te zeggen en hop van mening te veranderen. Had Johnson Claude gezegd dat die zes papers niet de juiste waren, dan was Claude zo met tien andere gekomen, en zijn die het niet, dan hier nog een paar.

Maar in tegenstelling tot Claude, heeft Johnson, als we hem vragen hoe hij tot zijn zeven papers gekomen is, een backstory, dan kan hij precies vertellen wat hij gedaan heeft, waarom, en waar de eventuele zwakheden zitten in het kiezen van papers. Dát is onderzoek!

Maybe the real research was the knowledge we gained on the way.

Ben je wetenschapper of heb je heel veel interesse in dit onderwerp? Dan is dit uitgebreide paper over de epistemologische risico's van AI gebruik echt een aanrader. Zij schrijven, dat het gebruik van AI onder andere als risico heeft:

marginalizing already neglected qualitative traditions such as critical, interpretive, and reflexive methodologies, which are vital for preserving the richness of qualitative insights.

Met andere woorden: meer en sneller onderzoek willen doen gaat ten koste van diep denken. Who knew?

De struggle met digitaal lesmateriaal

Ik maak van alles voor het eerst mee op school dit jaar, omdat ik in mei dit jaar van school gewisseld ben. Na 10 jaar is het enorm leerzaam om eens te kijken hoe dingen elders gaan, zo blijf je als docent scherp! Eén van de nieuwe dingen die ik meemaak is dat ik dit jaar voor het allereerst lesgeef uit een digitale methode (die ik niet zelf heb gemaakt). Mijn oordeel na een paar weken is zeer negatief. Ik zeg niet dat ik er niet nog beter in kan worden, maar het valt me niet mee.

Eén van de dingen die erg lastig is, is goed zien waar leerlingen zijn in het leerproces. Als leerlingen uit een (werk)boek werken, is het redelijk duidelijk waar ze zijn: je kan aan hoe het boek openligt of aan plaatjes en kopjes bijna meteen zien waar ze zijn, en anders kijk je vlot even op een paginanummer.

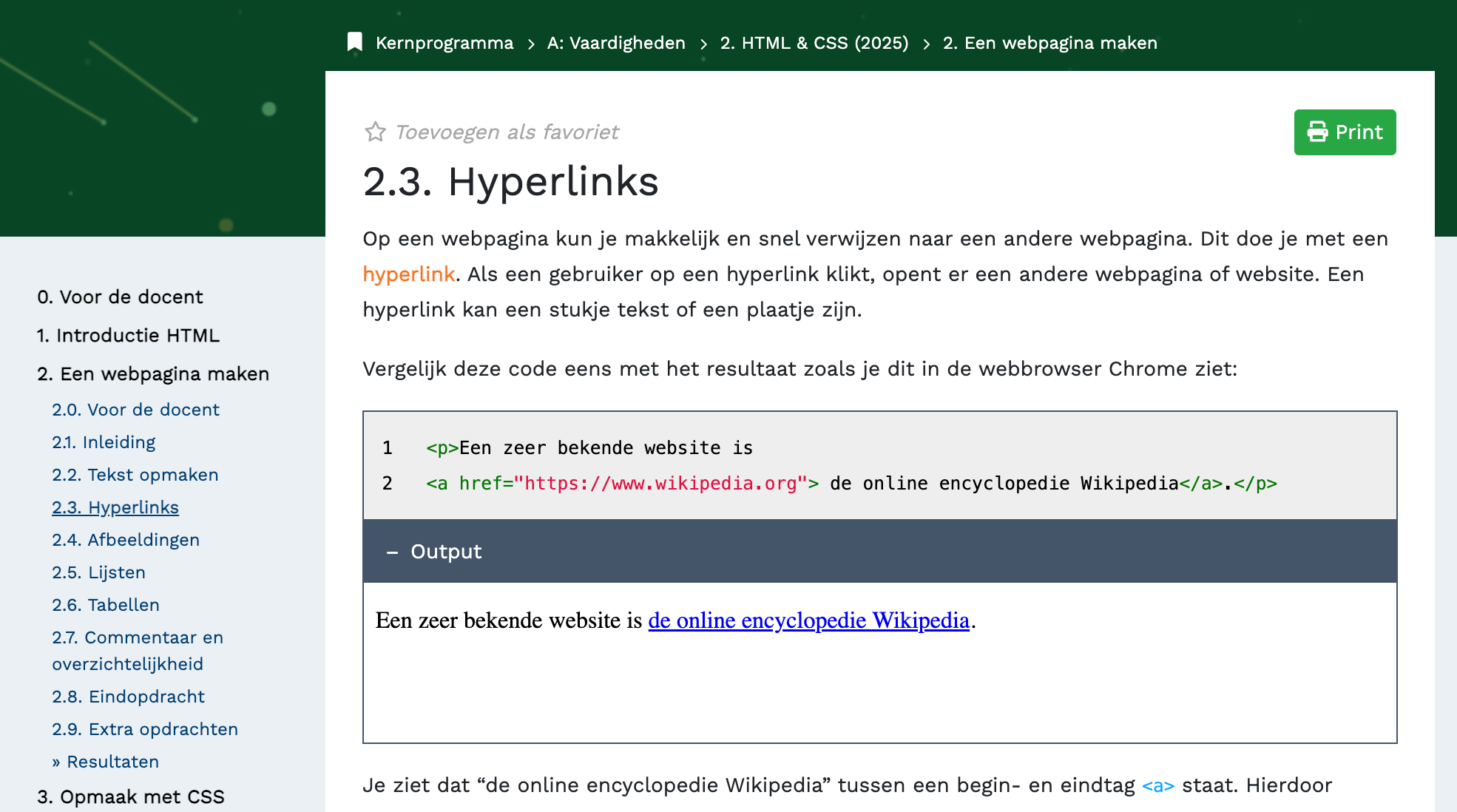

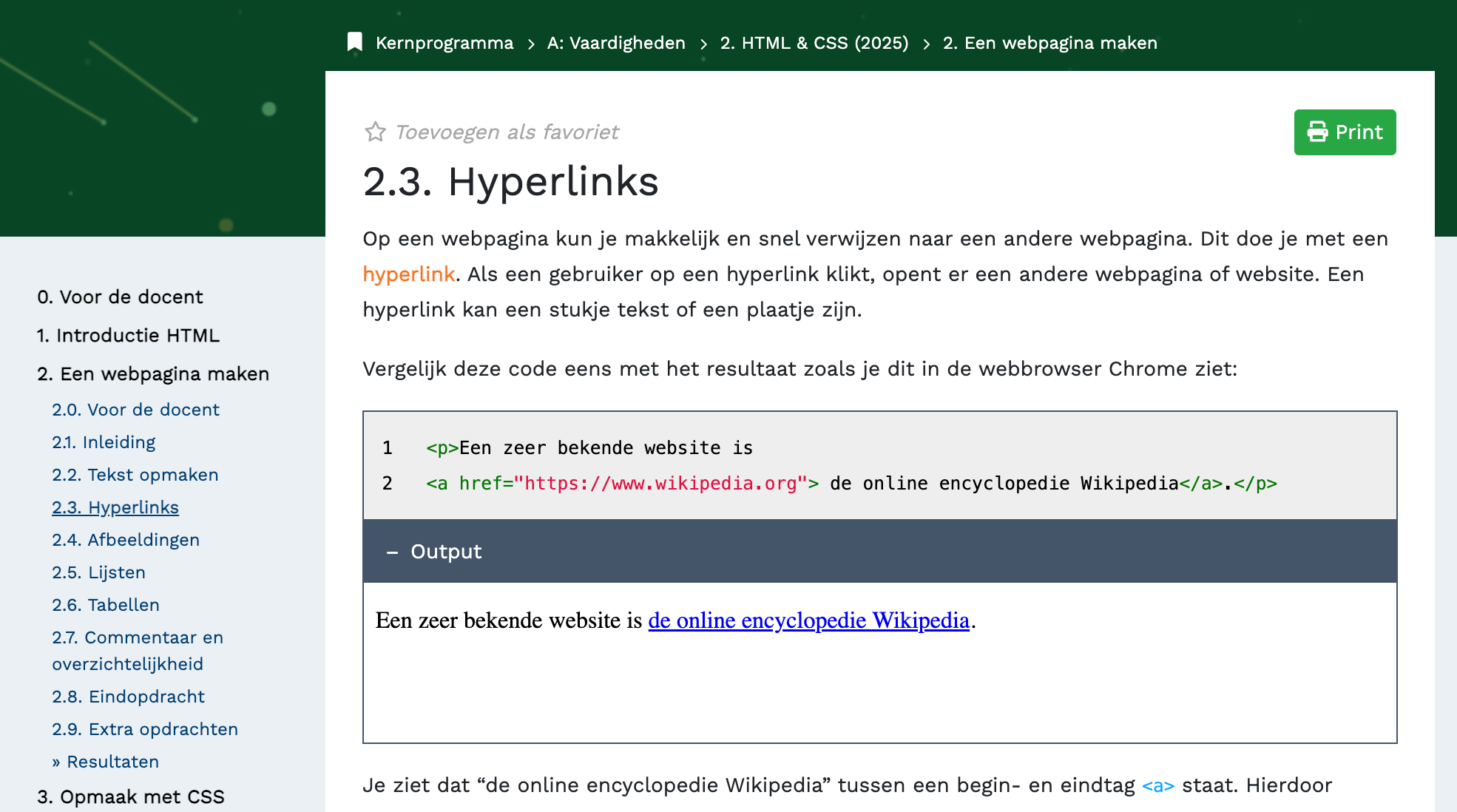

In een digitale methode vind ik dat veel moeilijker, want alleen door op hun scherm te kijken, zie ik niet waar ze zijn. Ik moet dan of lezen waar ze precies mee bezig zijn, en dan zelf onthouden hebben hoe ver dat in de huidige les is, of op een hele ondoorzichtige 'breadcrumb' lezen waar ze mee bezig zijn.

Bovenaan zie ik dan alleen hoofdstuk 2, en dan moet ik links in de balk weer kijken om te zien waar de leerling zit, 2.3. Maar dat is dus eigenlijk A.2.2.3, maar dat overzicht staat nergens. Ook hebben de onderdelen geen heldere namen. Is het blok 2, hoofdstuk 2, paragraaf 3? (Het middelste stuk wordt regelmatig hoofdstuk genoemd, de andere niet echt iets). Dit maakt het schier onmogelijk om met leerlingen te communiceren over het lesmateriaal, want we hebben het vocabulaire niet om uit te leggen wat ze moeten doen.

Ook is meekijken met leerlingen een hoop gedoe. Snapt een leerling iets niet, dan kan ik in een papieren (werk)boek terugbladeren en kijken of ze in een vorig hoofdstuk ook al vastliepen. Heb je dit gelezen, heb je dat gezien? Welke opgaves heb je gemaakt? Maar even snel bladeren is er in een digitaal systeem niet bij: Ga je terug naar een vorig hoofdstuk, dan begin je altijd bij het begin van het hoofdstuk. Ik kan dus niet van bijvoorbeeld 2.1 naar het hoofdstuk ervoor, 1.6. Dan moet ik eerst naar 1 en dan weer naar 1.6.

Ik zal ophouden met allerlei gedetailleerde voorbeelden geven, maar ik zou zo nog wel even door kunnen gaan met allerhande kleine hiccupjes.

Maar er zijn generieke lessen te trekken, die een veel grotere relevantie hebben dan ik versus deze lesmethode (Fundament).

Dit is namelijk geen kritiek op Fundament specifiek, want veel ervan zijn inherente problemen. Een papieren boek geeft nu eenmaal een andere modaliteit dan een online systeem en dat heeft voor- en nadelen. Alles heeft voor- en nadelen, maar een interessante vraag is bij wie de voordelen liggen en bij wie de nadelen. De voordelen zijn redelijk verdeeld, als je een foutje vindt, kan je het meteen fiksen, en zo blijft lesmateriaal up-to-date, en niet afdrukken scheelt geld en is beter voor de planeet. Met zulke argumenten wordt zo'n methode natuurlijk verkocht [[1]]. Maar de nadelen liggen alleen bij mij als docent en bij de leerlingen, wij moeten dealen met de inherente onoverzichtelijkheid.

En niet alleen moeten wij docenten met de ellende dealen, we zijn ook nog eens machteloos, omdat we in het systeem geen actor zijn. Het is overoverduidelijk dat deze methode niet gemaakt is door docenten die ermee lesgeven, want dan waren dit soort irritantheden wel verholpen. Toen ik bij college klaagde over dit gedoe kreeg ik meteen bijval van andere informaticadocenten die tegen exact dezelfde problemen aanliepen, zo had eentje al een leerling gehad die door de 2.2.3 verwarring ipv een hoofdstuk een hele module als huiswerk had gemaakt. Het is een klassiek voorbeeld van wat ze bij het Instituut voor briljante mislukkingen de 'verkeerde portemonnee' noemen, zelfs als iets als geheel beter is (en of dat zo is, dat weet ik in dit geval niet eens!) dan nog gaat dat vaak ten koste van een bepaalde groep.

En daar is de parallel te trekken naar AI, scholen worden nu ook op allerhande manieren overtuigd om wat met AI te doen, bijvoorbeeld de push van Google over gepersonaliseerde schoolboeken, voor iedere leerling een eigen tekst op eigen niveau. Zit er af en toe een Aracari tussen... tsja, jammer maar helaas, zoek jij maar even op of dat wel een vogel is. Het echte werk daarvoor zal straks voornamelijk door leraren gedaan moeten worden, dat zeg ik niet alleen, dat laat onderzoek ook zien zoals ik al eerder schreef over het werk van Neil Selwyn. Die docenten zijn machteloos zijn om de systemen (zowel technisch als sociaal als financieel) zo aan te passen dat dingen wel werken.

[[1]]: In het geval van informatica is de situatie trouwens nog gekker, want er zijn in Nederland alleen digitale methodes! Ik kan dus niet eens kiezen voor papier. Alsof leren over de digitale wereld per definitie op een digitale manier moet.

"Als het niet goed is, stoppen we er weer mee"

Onlangs deed ik op de VU mee aan een werkgroep over AI in het onderwijs, ik mag er niet te veel over zeggen want dat was de afspraak van deze meeting, maar het was buitengewoon interessant omdat het me een inkijkje gaf in hoe 'de VU' denkt over de inzet van AI, althans de gremia die gaan over het gebruik ervan. Ik was helaas de enige docent bij het overleg dus ik zat daar alleen met beleidsmakers (en de student die zou komen had het ook laten afweten).

Het is duidelijk dat het perspectief is (niet alleen op de VU, natuurlijk) we moeten het gewoon proberen, en als het niet werkt, dan stoppen we er gewoon weer mee. Sterker nog, alleen door te experimenteren komen we erachter of het werkt. Nu is dat in de basis natuurlijk al onzin, zo schreef ik al vaker, en Johannes Visser ook.

Vaak genoeg zijn er morele of praktische redenen waarom we iets niet doen, zonder het ooit te proberen. Maar voor de VU vind ik dat echt extra droevig. Wij hebben voor het hoofdgebouw tegeltjes liggen van alle 17 VN doelen, waaronder, Quality Education, Clean Water and Climate Action en Reduced Inequality [[2]]. Als je dat serieus neemt, dan kan je gewoon geen AI gebruiken, dus of wip in godsnaam die tegeltjes eruit, of stop met het propageren van AI, allebei is lelijk.

Maar los van de observatie dat je prima dingen links kan laten liggen zonder ze te proberen, zijn er nog een hoop andere problemen rondom deze propositie. Ik noem er drie, want ik ga, heus echt hand op mijn hart, proberen, mijn nieuwsbrieven korter te maken.

1. Normaliseren van de inzet van AI.

Zoals we ook zagen in een heel mooi en heel openhartig stuk van de ombudsman van NRC, met alleen al het suggereren van, of een stap verder, experimenteren met, een AI-bot, ook als die het later niet goed genoeg blijkt te doen, zijn we het gebruik aan het normaliseren. De ombudsman schrijft dat hij zich er ongemakkelijk bij voelt om "de lezer informatie geven met een disclaimer dat er fouten in kunnen staan." Je verplaatst dan immers de verantwoordelijkheid van het controleren naar de lezer. "Het staat ook op gespannen voet met de NRC Code."

Dat geldt net zo goed voor het hoger onderwijs, waar, ondanks dat we allemaal weten dat hallucinaties erbij horen, ook bij mijn werkgever nog steeds workshops gegeven worden die je helpen AI te gebruiken voor het "formuleren van leerdoelen, het ontwerpen van cursussen, het ontwerpen van lesplannen, het ontwerpen van rubrics, het ontwikkelen van beoordelingsmateriaal of zelfs powerpoints".

Dat lijkt mij dus op gespannen voet staan met "quality education", want verwachten we nu echt van docenten die al zo onder (tijds)druk staan, dat ze alles wat uit de bots komt, kunnen controleren?

Maar erger nog is dus de alles ondermijnende notie dat het maken van powerpoint een klein bijzaakje is dat de computer wel voor je kan doen, in plaats van een diepe cognitieve activiteit waarin je als expert diep nadenkt over welke stof je behandelt, hoe je die aanbiedt, en in welke volgorde.

De principiële horde ligt op universiteiten in Nederland al mijlenver achter ons.

2. Wat betekent "het werkt niet"?

Het was iets piepkleins, maar één van de deelnemers aan de vergadering op de VU noemde als idee het inzetten van een chatbot om interactie met de syllabus van vakken voor studenten makkelijker te maken. Tussen neus en lippen door noemde hij dat zo'n syllabus nu, op 'Learning Management Systeem' Canvas (een soort Magister voor studenten), vaak zo onoverzichtelijk zijn, dat een AI bot misschien wel soelaas zou bieden.

Nou, dan zakt je broek toch af? Want waarom zitten docenten eigenlijk op Canvas, uit vrije wil soms? Nee, omdat we door dezelfde soort innovatiecentra die ons nu LLMs door de strot duwen, zijn gedwongen daar onze informatie te delen. Voordat die systemen er waren gebruikte docenten hun eigen website, of (iets dat geheel en al uitgestorven lijkt op de moderne universiteit) dictaten. Dat waren simpele boekjes met teksten en opdrachten die je voor een knaak-50 bij een loketje in de krochten van de universiteit kon kopen. Heel overzichtelijk, want op papier (zie ook boven). De voordelen van papier boven digitaal lezen zijn trouwens uitgebreid onderzocht, ook al in de tijd voordat LMS-en werden ingevoerd, dus het is niet alsof ze dat toen niet ook al wisten. Al midden jaren '90 bleek dat uit onderzoek. Zie bijvoorbeeld hoofdstuk 7 van The Shallows van Nicolas Carr voor een uitgebreide literatuurreview, die hij als volgt inleidt:

Dozens of studies by psychologists, neurobiologists, educators, and Web designers point to the same conclusion: when we go online, we enter an environment that promotes cursory reading, hurried and distracted thinking, and superficial learning.

Stappen we nu af van Canvas omdat het onoverzichtelijk is, hetgeen dus uit onderzoek blijkt al 30 jaar, en ook uit onze eigen ervaringen? Nee, au contraire mon ami, we gaan technologie op de technologie sausen om de problemen te verhelpen die de technologie veroorzaakt heeft.

Vergeef me dus dat ik niet geloof dat we van de LLMs afscheid gaan nemen als ze niet goed blijken te werken want niemand definieert wat dat betekent. Kijk het kan wel hoor, in Zuid-Korea rollen ze de AI-boeken al weer terug, dus misschien moeten we hoop houden, maar gegeven dat, kunnen we niet beter nu al ophouden?

3. We kunnen de meeste problemen al oplossen (soms zelfs technologisch)

En het meest frustrerende is nog wel dat de plekken waar ik zie dat AI op de universiteiten ingezet wordt, andere technologie het probleem ook prima op zou lossen. Dictaten zijn daar een voorbeeld van, maar ook digitale technologie. I can't believe dat ik hier Eric Schmidt citeer—meneer AI gaat alle klimaatproblemen oplossen, ohnee toch niet—maar hij heeft een punt in zijn recente oped in New York Times dat de focus van Silicon Valley (die dus ook het discourse in het hoger onderwijs dicteert) ervoor zorgt dat we "bypassing crucial opportunities to use the technology that already exists".

Ja, maar we kunnen AI gebruiken om cijfers te geven? Ah ja, heb je al multiple choice gebruikt? Een prima manier om na te kijken, die, zo laat een metastudie zien, heel vaak net zo goed werkt als open tekst vragen, als je ze maar vergelijkbaar opstelt.

Ik weet het meeste van informatica-didactiek, maar daar kan ik dan ook wat concretere uitleg geven. We laten studenten vaak "vrij" programmeren, waarbij ze alle code zelf moeten typen. Dat is moeilijk en frustrerend, bijvoorbeeld omdat je alle haakjes en punten goed moet zetten. En het nakijken is een enorme tour, want je moet niet alleen bekijken of studenten het programmeerprobleem hebben opgelost, maar ook of ze dat wel op de goede manier doen, met de juiste concepten, en vaak kijken er ook nog ouderejaars naar of het er een beetje netjes uitziet. Het is bijna niet te geloven als je niet in dit vakgebied werkt, maar er zijn hiervoor tientallen, zo niet honderden programma's geprogrammeerd door informatica-wetenschappers. Ik durf niet te schatten hoeveel uur daaraan besteed is maar het moet in de tienduizenden lopen echt, omdat ze allemaal hun eigen systeem willen maken. Dat is leuk en dan kan je het precies doen zoals je wil.

Maar, het kan veel makkelijker en sneller met Parson's problems, puzzels waarin je regels code op volgorde moet leggen. Ook die werken net zo goed als open programmeervragen:

We find notable correlation between Parsons scores and code writing scores. We also make the case that marks from a Parsons problem make clear what students don't know (specifically, in both syntax and logic) much less ambiguously than marks from a code writing problem.

Het is echter al jaren een uphill battle om docenten informatica hiervan te overtuigen, het geloof dat vrij programmeren tot meer programmeervaardigheid leidt zit zo diep dat ik niet echt dat ik het nog meemaak dat we daarvan afstappen. Dat geldt trouwens voor andere dingen ook, bijvoorbeeld het geloof dat het zelf doen van onderzoek en daarover een scriptie schrijven studenten meer leert over onderzoek dan er goede kritische reflecties over lezen. Aangezien dat laatste in de meeste informatica opleidingen uitblijft, heeft dat eerst wat mij betreft ook maar zeer weinig zin. En toch blijven we het doen.

Door AI begint de strijd weer opnieuw, want nu lijkt er opeens een oplossing te zijn voor al dat nakijkwerk, terwijl veel van het werk dus prima op een "ouderwetse" manier zou kunnen worden gedaan, met simpele algoritmes.

En eigenlijk zit het issue nog dieper zit het issue, want het idee dat we kunnen nakijken met AI zorgt voor een hernieuwde honger naar meer nakijken, terwijl we ook zouden kunnen overwegen om uberhaupt eens wat minder te gaan nakijken!

[[2]]: Nu ik dit schrijf zie ik hoe suf dat doel eigenlijk is. Niet eens "Geen inequality", nee dat halen we nooit. Doe dan maar gewoon minder.

Events

Je kan me de komende weken weer op een aantal plekken treffen:

- Donderdag 6 november, I&I conferentie, Hogeschool Utrecht

- Vrijdag 7 november Uitreiking Prijs van de Onderwijsjournalistiek waar ik een praatje mag geven, Spui25

- Zaterdag 8 november boeklaunch met Jim en Dolf Jansen , Boom Chicago

- Dinsdag 18 november boeklaunch Niet onze AI, Felix Meritis

Goed Nieuws

Het verzet tegen AI groeit, aldus Laurens Vreekamp, die daarbij ook held Iris van Rooij noemt, en ons paper!

En de Python foundation weigert een grant van 1.5 miljoen dollar, omdat ze dan niks meer aan diversiteit mogen doen. Dat zijn de ruggengraten die we nodig hebben! Een contrast met Google die gewoon braaf diversiteitsprogramma's terugrolt.

Sam Altman zegt zelf geen chatGPT te gebruiken, maar pen en papier! Nou dan weten we eigenlijk genoeg toch, over hoezeer hij gelooft dat het superintelligentie is? Hij staat hiermee natuurlijk in een lange traditie, zo liet Steve Jobs zijn kinderen geen iPad gebruiken, en zocht onze eigen Alexander Klöpping een tijdje terug nog een (menselijke!) assistent.

Geloof jij dus deze mensen nog, die hun eigen hypes niet eens geloven...?

Slecht nieuws

Het waren geen fijne verkiezingen voor de vrouwenzaak, helaas. Vrouwen waren maar nauwelijks aan het woord op TV, bleek uit een droevige analyze in NRC. De show met het hoogste percentage vrouwen RTL Nieuws komt niet verder dan 38%. En, misschien nog wel erger! Stichting Stem op een vrouw werd op de dag voor de verkiezingen geddost, en zo verhinderde ze misschien wel dat mensen op onderzoek gingen naar op welke vrouw ze strategisch moesten stemmen.

En over vrouwen gesproken, we moeten het onrecht blijven aanvechten waarbij mannen systematisch met de achternaam beschreven worden, maar vrouwen niet, zo legde Trouw maar weer eens pijnlijk bloot. Kijk, daarvan denk ik: een simpel botje kan dit zo voor je checken en je redelijk betrouwbaar waarschuwen als je dit per ongeluk doet. Dat is een nuttige inzet van AI!

Ik las een tijdje terug het boek Erasing History, nouja in alle eerlijkheid las ik het maar half, want het staat vol met dingen die we allemaal wel weten, althans ik wel. Maar nu zien we in Amerika toch in full force gebeuren wat Stanley beschrijft, en dan niet eens door de overheid zelf, maar door een miljardair, Musk met zijn Grokipedia. Marie-José Klaver legt in een heel mooi stuk uit hoe subtiel dat kan gaan, niet zozeer met leugenachtige feiten, maar door de focus wel of niet op de persoonlijke karakteristieken te leggen. Lees dat stuk en snap nog beter hoe misleiding werkt!

The purpose of a system is what it does. Dat is (helaas) de manier waarop ik naar de wereld kijk, en het geeft zo vaak inzicht. Bedrijven ontslaan mensen onder het mom van "AI kan het werk" en nemen ze dan stilletjes weer aan, voor veel minder salaris. Het is geen gek bij-effect, het is een doel van AI.

Geniet van je boterham!

English

Model collapse

I mentioned the different AI bubbles a few weeks ago: the investment bubble, the hype bubble, and the infrastructure bubble. The investment bubble is easy to explain, it has existed for centuries: one day, the money will simply run out, and we cannot keep pouring everything into AI. According to hero Ed Zitron, OpenAI will need another $400 billion in the next 12 months alone. The infrastructure bubble is also quite clear. Unlike, for example, the internet infrastructure that remained after the dot-com bubble, GPUs have a very short lifespan, only about 1 to 3 years. So once this bubble bursts, we will have nothing left to do something with.

But that third bubble, the hype bubble, is more elusive. I keep hearing from people that AI is going to get much better, even though Sam Altman himself says that's not the case at all, that hallucination will always be part of LLMs. We are so used to technology that keeps getting better and better, and we hear that story constantly from AI hypers, that we continue to believe it.

However, researchers from Oxford and Cambridge, among others, show in a recent Nature paper that LLMs, as they read more synthetic data, will exhibit model collapse:

Model collapse is a degenerative process affecting generations of learned generative models, in which the data they generate end up polluting the training set of the next generation. Being trained on polluted data, they then mis-perceive reality.

Now, it could be that the model improves with synthetic data, if it happens to be very accurate. But, they say, that is usually not the case:

More often than not, we get a cascading effect, in which individual inaccuracies combine to cause the overall error to grow.

The authors give an example that illustrates quite well how such an incestuous LLM behaves:

Trying to program out those crazy repetitions only makes the result worse. And, as another paper wrote, LLMs can also get brain rot from bad data (although I'm not fond of this term because it is now so strongly associated with humans).

The future doesn't look very hopeful, because we're already almost there with that bad and synthetic data! On the blog of visualization tool Graphite, we can read that more than half of the new articles on the internet now come from AI. The dead internet theory, once a crazy conspiracy theory, is starting to sound credible. After all, Google itself has already said that "the open web is in decline" (Dutch).

And then there's the issue of unintentional contamination of datasets, although you might wonder how accidental it really is when it's as obvious as the Titanic hitting the iceberg...

At least as problematic is research by Anthropic itself, which shows that with 250 documents, you can already help an LLM over the hump, regardless of how large the dataset is on which it is trained. Now, according to them, that's not a big deal, as the model will at most start talking gibberish, but they mention it anyway, which is nice of them. Unlike the researchers at Anthropic, I think this is a significant risk, because it further undermines the possibility of obtaining good information!

Funny detail, by the way, Anthropic's post doesn't render properly (see below), which immediately makes me wonder... Is this a poisoned document? Or is it gibberish? Am I part of the next test?

Writing as ‘theory building’

As I wrote earlier, my research currently focuses most on the question of why computer science is the way it is, and what worldview emerges in computer science education, and thus in computer science culture.

This raises questions such as what does and does not belong to the computer science canon. Sometimes this concerns people. For example, during my studies, I had never heard of Joseph Weizenbaum and his sharp criticism of the culture of computer science and chatbots (but then again, I studied during an AI winter). Sometimes it concerns which aspects of a researcher we learn about.

We all know Danish computer scientist Peter Naur from the Backus-Naur form, which can be used to describe programming languages. But he also wrote a brilliant paper called Programming As Theory Building. It is very short, you can read it in about an hour, but it is full of truths that are still useful today.

In this paper, Naur writes that when you learn something, it is not only about being able to do something, but also about being able to explain and defend it:

the knowledge a person must have in order not only to do certain things intelligently but also to explain them, to answer queries about them, to argue about them, and so forth.

He calls this developing a theory (theory is a bit of a strange word in this context, because it can mean many different things, but I will go along with this term for now):

A person who has a theory is prepared to enter into such activities; while building the theory, the person is trying to get it.

In his paper, Naur argues that when you think about something, and I am generalizing here from programming to all kinds of thinking, you acquire theories about how that something works, but that you can then also explain why it works that way, or why the way it works is really the smartest way to do it.

Now, of course, there are plenty of reasons not to want to use AI: devastating climate impact—just this week we read again about Microsoft building AI data centers and taking no responsibility for the environmental impact—bias, more power for tech bosses who are fans of Trump, etc. But this is a much deeper reason: the systematic confusion of the output of work with what you learn from that work. For example, I saw this post on BlueSky from Todd Johnson, a professor of biomedical informatics:

We spent months doing a careful lit review with help from a librarian, PubMed, and Google Scholar. After we had completed the work and whittled the 7K+ citations down to only 7 that met our criteria, I asked Claude the question we were trying to answer. It found 6 of the 7 and wrote a great report.

I find it tiring to have to keep explaining this, but as a scientist, you not only have to deliver knowledge, you also have to stand for that knowledge, stand for why you chose exactly those seven papers, and not, with the help of other criteria, arrived at some others. It is precisely this explainability that an algorithm lacks, because it clearly did not spend months reading, deliberating, and weighing the right criteria and papers. Do we really want scientists, when we ask them how they arrived at a conclusion, to say: Claude said so?

An algorithm has no inner state, no memory, and no traceable process that leads to conclusions. We all know this because when we encounter another hallucination and ask questions, the AI is always ready to say sorry and change its mind. If Johnson had told Claude that those six papers weren't right, Claude would have come up with ten others, and if those weren't right, a few more.

Contrary to Clause though, Johnson has a story, if we ask him how he came up with his seven papers; he can tell us exactly what he did, why, and where the potential weaknesses lie in choosing those papers and not others. That's research!

Maybe the real research was the knowledge we gained along the way.

Are you a scientist or very interested in this topic? Then this comprehensive paper on the epistemological risks of AI useis highly recommended. They write that one of the risks of using AI is:

marginalizing already neglected qualitative traditions such as critical, interpretive, and reflexive methodologies, which are vital for preserving the richness of qualitative insights.

In other words: the desire to do more research quicker comes at the expense of deep thinking. Who knew?

My struggle with digital textbooks

I am experiencing everything for the first time at school this year, because I changed to a different school last May. After 10 years, it is extremely insightful to see how things are done in different places; it keeps you sharp as a teacher! One of the new things I am experiencing is that this year, for the first time, I am teaching with a digital textbook (that I did not create myself). My opinion after a few weeks is not at all positive. I'm not saying I can't get better at it, but I'm finding it difficult.

One of the things that I find difficult is seeing where students are in their learning process. When students are working from a (work)book, it is fairly clear where they are: you can see is by how the book is opened, or by looking at the pictures and headings, and if not, you can quickly check the page number.

I find this much more difficult with a digital system, because just by looking at their screen, I can't see where they are. I then have to either read what they are working on and remember how far that is in the current lesson, or read a very unclear ‘breadcrumb’ to see what they are working on.

At the very top, I only see chapter 2, and then I have to look again in the bar on the left to see where the student is, 2.3. But that is actually A.2.2.3, but that overview is nowhere to be found. Also, the sections do not have clear names. Is it block 2, chapter 2, paragraph 3? (The middle part is regularly referred to as a chapter, the other parts not really have names). This makes it almost impossible to communicate with students about the teaching material, because we don't have the vocabulary to explain what they need to do.

It is also a lot of hassle to look over students' shoulders. If a student does not understand something, I can flip back through a paper (work)book and see if they also got stuck in a previous chapter. Have you read this, have you seen that? Which exercises have you done? But quickly flipping through pages is not possible in a digital system: if you go back to a previous chapter, you always start at the beginning of the chapter. So I can't go from 2.1 to the previous chapter, 1.6, for example. I have to go to 1 first and then back to 1.6.

I'll stop giving all kinds of detailed examples, but I could go on and on with all kinds of minor hiccups.

However, there are generic lessons to be learned that are much more relevant than me versus this textbook (Fundament).

This is not a criticism of Fundament specifically, because many of these are inherent problems. A paper book simply offers a different modality than an online system, and that has advantages and disadvantages. Everything has advantages and disadvantages, but an interesting question is who benefits from the advantages and who suffers from the disadvantages. The advantages are fairly evenly distributed: if you find a mistake, you can fix it immediately, and this keeps teaching materials up to date, and not printing saves money and is better for the planet. Such arguments are naturally used to sell these teaching materials [[11]]. But the disadvantages lie solely with me as a teacher and with the students; we have to deal with the inherent lack of clarity.

And not only do we teachers have to deal with the hassle, we are also powerless because we are not actors in the system. It is abundantly clear that this textbook was not created by teachers who use it, because if it had been, these kinds of annoyances would have been fixed. When I complained about this mess, I immediately received agreement from other teachers who encountered exactly the same problems. One of them had already had a student who, due to the 2.2.3 confusion, had done an entire module as homework instead of a chapter. It is a classic example of what they call the ‘wrong wallet’ at the Dutch Institute for Brilliant Failures. Even if something is better overall (and I don't even know if that is the case here!), it is often at the expense of a certain group.

And there's a parallel to be drawn with AI. Schools are now being persuaded in all kinds of ways to do something with AI, for example, Google's push for personalized textbooks, with each student having their own text at their own level. If there's an Aracari in there somewhere... Well, too bad, you'll have to look up whether that's a bird. The real work will soon have to be done mainly by teachers. I'm not the only one saying this; research also shows this, as I wrote earlier about the work of Neil Selwyn (Dutch). Those teachers are powerless (technically, socially, and financially) to improve the systems.

[[11]]: In the case of computer science, the situation is even crazier, because in the Netherlands there are only digital textbooks! So I can't even choose paper. As if learning about the digital world must, by definition, be done digitally.

"If LLMs don't work, we'll stop using them"

I recently participated in a working group at VU on AI in education. I can't say too much about it because that was the agreement for this meeting, but it was extremely interesting because it gave me an insight into how my university thinks about the use of AI, at least the committees that decide on its use. Unfortunately, I was the only teacher at the meeting, so I sat there alone with policymakers (and the student who was supposed to come didn't show up either).

It is clear that the perspective (not only at the VU, of course) is that we should just try it, and if it doesn't work, we'll just stop. In fact, only by experimenting can we find out if it works. Now, that is nonsense, of course, as I have written several times, and Johannes Visser has also written (all these in Dutch, sorry!).

Often enough, there are moral or practical reasons why we don't do something without ever trying it. But for the VU, I find this particularly sad. We have tiles in front of the main building depicting all 17 UN goals, including Quality Education, Clean Water and Climate Action, and Reduced Inequality [[12]]. If you take those seriously, then you simply cannot use AI. So either remove those tiles, for goodness' sake, or stop promoting AI; you can't eat your cake and have it too.

But apart from the observation that you can easily ignore things without trying them, there are other problems surrounding this proposition. I'll mention three, because I'm really really going to try to make my newsletters shorter.

1. Normalizing the use of AI.

As we also saw in a strong and very candid piece by the ombudsman of Dutch newspaper NRC, just by suggesting, or going a step further, experimenting with, an AI bot, even if it later turns out not to perform well enough, we are normalizing its use. The ombudsman writes that he feels uncomfortable about "providing readers with information with a disclaimer that it may contain errors." After all, this shifts the responsibility for checking to the reader. "It is also at odds with the NRC journalistic Code."

This applies just as much to higher education, where, despite the fact that we all know that hallucinations are part of the process, my employer still offers workshops that help you use AI to "formulate learning objectives, design courses, design lesson plans, design rubrics, develop assessment materials, or even PowerPoint presentations."

To me, that seems to be at odds with "Quality education", because do we really expect teachers, who are already under so much pressure (and time constraints), to be able to check everything that comes out of the machines?

But even worse is the undermining notion that creating PowerPoint presentations is a minor task that the computer can do for you, rather than a deep cognitive activity in which you, as an expert, think deeply about what material you are covering, how you are presenting it, and in what order.

Theis fundamental hurdle has already been taken at universities in the Netherlands.

2. What does "it doesn't work" mean?

It was a tiny thing, but one of the participants in the meeting at VU suggested using a chatbot to make it easier for students to interact with the course information. He casually mentioned that a course syllabus on the 'Learning Management System' Canvas is now often so confusing for students that an AI bot might offer a solution.

Seriously? Why do teachers put their syllabi on Canvas, because they love these systems? No, because we are forced to share our information there by the same kind of innovation centers that are now pushing LLMs down our throats. Before those systems were in use, teachers used their own websites or (something that seems completely extinct in modern universities) used paper lecture notes. These were simple booklets with texts and assignments that you could buy for a few bucks at the university. They worked well, because they were on paper (see also above). The advantages of paper over digital reading have been extensively researched, even before LMSs were introduced, so it's not as if they didn't know that back then. Research in the mid-1990s already showed this. See, for example, chapter 7 of The Shallows by Nicolas Carr for an extensive literature review, which he introduces as follows:

Dozens of studies by psychologists, neurobiologists, educators, and Web designers point to the same conclusion: when we go online, we enter an environment that promotes cursory reading, hurried and distracted thinking, and superficial learning.

Are we now abandoning our LMS's because digital systems are confusing, which has been shown by research for 30 years, and also is our own lived experience and that of our students? No, au contraire mon ami, we are going to slap technology on top of technology to remedy the problems that technology has caused.

So forgive me for not believing that we will say goodbye to LLMs if they turn out not to work well, because no one defines what that means. Look, it is possible, in South Korea they are already rolling back AI books, so maybe we should remain hopeful, but we could also just stop now.

3. We can already solve most problems (sometimes even technologically)

And the most frustrating thing is that in the areas where I see AI being used in universities, other technology would also solve the problem just fine. Lecture notes are one example, but so is digital technology. I can't believe I'm quoting Eric Schmidt here—Mr. AI is going to solve all climate problems, oh oopsie I was wrong —but he has a point in his recent op-ed in New York Times that the focus of Silicon Valley (which also dictates the discourse in higher education) causes us to "bypass crucial opportunities to use the technology that already exists."

We can use AI to give grades? Oh, have you tried multiple choice? It's a fine way to test students too, and a meta-study shows that it often works just as well as open-ended questions, as long as you set them up in a comparable way.

I know most about computer science didactics, but I can give a more concrete explanation there. We often let students program open form, requiring them to type all the code themselves. That is difficult and frustrating, for example because you have to put all the brackets and periods in the right place. And checking the work is a huge task, because you not only have to check whether students have solved the programming problem, but also whether they have done so correctly, using the right concepts, and often senior students also check whether it looks neat and tidy. It's almost unbelievable if you don't work in this field, but there are dozens, if not hundreds, of programs written for this purpose by computer scientists. I wouldn't dare to estimate how many hours have been spent on this, but it must be in the tens of thousands, because they all want to create their own system. That's fun, and it allows you to do exactly what you want.

However, it can be done much more easily and quickly with Parson's problems, puzzles in which you have to put lines of code in order. These also work just as well as open programming questions:

We find notable correlation between Parsons scores and code writing scores. We also make the case that marks from a Parsons problem make clear what students don't know (specifically, in both syntax and logic) much less ambiguously than marks from a code writing problem.

However, it has been an uphill battle for years to convince computer science teachers of this. The belief that free programming leads to greater programming skills is so deeply ingrained that I don't really think I will live to see us move away from it. This also applies to other skills by the way, outside of programming, such as the belief that doing research themselves and writing a thesis about it teaches students more about research than reading good critical reflections on it. Since the latter is not part of most computer science programs, I don't see much point in doing the former. And yet we continue to do it.

AI is renewing the debate, because now there suddenly seems to be a solution for all that grading work, while much of the work could be done in the "old-fashioned" way, with simple algorithms.

And actually, the issue goes even deeper, because the idea that we can grade with AI creates a renewed hunger for more grading, while we could also consider grading less in the first place! (Dutch)

[[12]]: As I write this, I realize how silly that goal actually is. Not even "No inequality"... No, we'll never achieve that. Let's just aim for "less".

Good News

Resistance to AI is growing, according to Laurens Vreekamp, who also mentions hero Iris van Rooij, and our paper!

And the Python Foundation is refusing a $1.5 million grant because it would prevent them from doing diversity work. Those are the backbones we need! A contrast with Google that simply rolls back diversity programs.

Sam Altman says he doesn't use ChatGPT, but pen and paper! Well, that tells us enough about whether he believes it's super-intelligent, doesn't it? Of course, he's following in a long tradition: Steve Jobs didn't let his children use iPads.

So why should we believe these people who don't even believe their own hype...?

Bad news

Unfortunately, it was not a good election for women's issues. Women hardly appeared in Dutch talkshows, according to a sad analysis in NRC. The show with the highest percentage of women, RTL Nieuws reached only 38%. And, perhaps even worse, the "Stem op een vrouw" foundation who aims to help people pick women to vote for across party lines suffered from a ddos attack the day before the elections, which may have prevented people from researching which woman they should strategically vote for.

And speaking of women, we must continue to fight the injustice of men being systematically called by their last names, and women by their first, as Trouw once again painfully exposed. Here I think a simple AI system could check this and warn you fairly reliably if you accidentally do this. That's a useful application of AI!

A while back, I read the book Erasing History. Well, to be honest, I only read half of it, because it's full of things we all know, at least I do. But now we're seeing in full force in America what Stanley describes, and not even by the government itself, but by a billionaire Musk, with his Grokipedia. Marie-José Klaver explains in a very nice Dutch piece how subtle this can be, not so much with false facts, but by focusing or not focusing on personal characteristics. Read that piece and understand even better how subtle deception works!

The purpose of a system is what it does. That is (unfortunately) the way I look at the world, and it so often provides insight. Companies lay off people under the guise of "AI can do the work" and then quietly rehire them for much less pay. It's not a weird side effect, it's one of the goals of AI.

Enjoy your sandwich!

Member discussion